Story//Andy Levinsky. Photos//Courtesy Not Impossible Labs.

His story began in Phoenix and Southern California before winding its way through such far-flung destinations as Sudan, Kenya, India and Mexico.

Today, however, Mick Ebeling has landed at a resort and casino near Boston where he will be speaking to hundreds of sales professionals for the tech company Nuance Communications. Never mind that Ebeling has no formal training in sales or that his company, Not Impossible Labs, has become known for intentionally low-tech (and low cost) innovations. According to Nuance, Ebeling was chosen to drive home the message “that everyone, everywhere, has the power to make a positive impact on someone else’s life.”

In other words, Ebeling is here for his skills as a motivational speaker, a role for which he checks all of the boxes: author (Not Impossible: The Art and Joy of Doing What Couldn’t Be Done, blurbed by gurus like Deepak Chopra); representation by A-list speakers bureau; requisite TED Talk.

Yet Ebeling acknowledges “I have no credentials behind my name.” By this, he means, “I do not educationally and experientially possess the knowledge to solve all the problems we tackle” and “typically, the solution is not in me solving it but in [my] finding brilliant people who can.”

And once this non-credentialed networker has brought together the inventors and other great minds in science and technology to solve “insurmountable” challenges, does he have any idea what they’re talking about? “I know enough to make myself dangerous,” he says, “and to challenge when people say ‘That’s not possible.’”

"…typically, the solution is not in me solving it but in [my] finding brilliant people who can."

Beyond convening and cheerleading, Ebeling brings narrative skills developed earlier in his career, when he produced commercials, music videos and title sequences for movies like Quantum of Solace (James Bond) and The Kite Runner. Although Ebeling has the title of CEO for Not Impossible Labs (and its non-profit foundation), a more informative description of his role might be Chief Altruist and Allegorist.

“It is the story that makes an invention compelling,” he wrote in his book. “That’s how change happens: through a clear and simple relatable story.” Every manifestation of the Not Impossible “brand,” from videos and podcasts to Ebeling’s stump speech (which is basically an abbreviated version of the book), tells the stories of those who create life-changing devices and those who benefit from them. More than ten years since Not Impossible’s inception, the number of these stories is rapidly proliferating, but Ebeling nearly always begins with two:

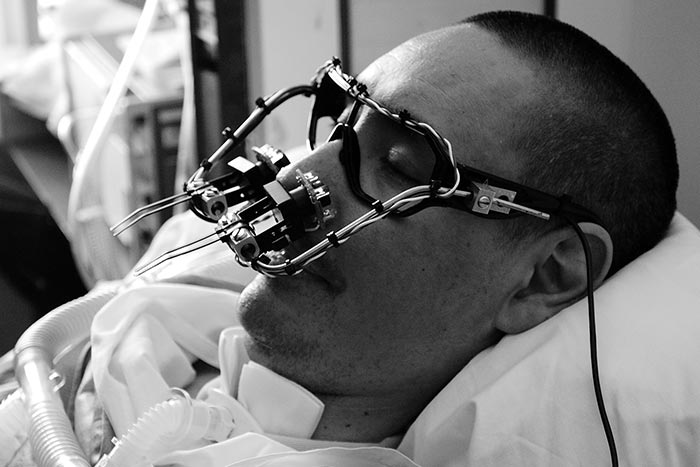

Temp One with a Not Impossible Eye Writer.

Tony Quan, a.k.a. Tempt One, was an L.A. graffiti artist, or tagger. As with street artists from Keith Haring to Banksy, Tempt’s distinctive style began to attract the attention of the museum world but when he was diagnosed with ALS (Lou Gehrig’s Disease) in 2003, it appeared to be the end of a promising career. In 2007, Ebeling and his wife, Caskey, attended a benefit for the artist. Six months later, he had a feeling that, as he described in his book, “Something was nagging at me. Some kind of unfinished business…It was Tempt.” After meeting with Tempt and his family in the hospital, Ebeling was determined to find a way for the artist, who was immobile, to continue his work. He gathered a global group with eclectic expertise, from a hacker/programmer to an ocular reading specialist, and developed a device which enabled Tempt to communicate and create through eye movement.

“We didn’t have visions of revolutionizing the medical device industry,” Ebeling wrote. “We wanted to help Tempt. One person.” Yet they made The Eye Writer, as it was dubbed, from inexpensive components, accessible to all. From this invention came a company, (Not Impossible Labs), its guiding principle and de facto slogan (“Help One, Help Many”) and an open-source model to achieve it. Tempt’s story is interspersed with clips from “Getting up: The TEMPT ONE Story,” a 2012 documentary directed by Caskey, the co-founder and executive creative director of Not Impossible. When Ebeling mentions how this artist, who could not move or speak for years, was able to create his first new work of art, you can actually hear the audience getting choked up. Clearly, he has told this story so many times that he knows each applause line, yet he delivers it with a sense of spontaneity that suggests he still is moved himself.

If Tempt is Not Impossible’s origin story, Daniel’s is the rare sequel that is its equal. In South Sudan, a bomb severs the hands of 14-year-old Daniel Omar. Reading a Time Magazine article about Daniel and the doctor who saved his (and countless other) lives, Ebeling, the father of three young boys, thought, “’What if Daniel were my son?’” So, as he wrote, “In that moment, he became just that.”

This story has a large enough cast of characters for a Hollywood film and all of the drama. Ebeling and his team are on a mission to create new arms for Daniel using a 3-D printer. First, they must find him among the 70,000 denizens of what the UN described as “the most challenging refugee camp in the world.”

Daniel Omar grasping a ball with his prosthetic arm.

A 6-foot 5 basketball player who attended U.S. Air Force Academy in Colorado and signs his letters, “Take risks, Mick,” Ebeling didn’t seem deterred by the challenge. “I don’t just drop behind the enemy lines with a buck knife and a granola bar,” he explained. “I took precautions and we had contingency plans.”

According to Caskey, these included “a big pile of cash just in case we had to pay mercenaries to get him out.” She recalls that two weeks after he left Sudan, “the place where he was staying was bombed. He was working in an active war zone.”

Why put the life of his own kids’ father at risk for a stranger’s son? “Even with three children, he will not allow fear to ever deter him from doing what he thinks he is capable of,” Caskey says, “or is the right thing to do.”

Even his mother, Marge, who has “spoken up when I have concerns for his safety and his family,” confesses that “He expects this from me. Then the subject is changed.”

Pacing the stage in a gray t-shirt, black pants and a baseball cap, Ebeling looks like the kind of 49-year-old who would commute to work on a skateboard, his preferred mode of transportation to the office of Not Impossible in Venice, California, where he works with the organization’s fifteen member staff. The stories of the organization’s beneficiaries like Tempt and Daniel evoke the most visceral audience response, but a parallel narrative comes from its heroes: a patchwork of doctors and other scientists, engineers, hackers and technologists, who make the impossible possible. Most compelling of all is the story of their fearless leader.

ORIGIN STORY

The comic book writer Matt Fraction (born Frichtman), who met Ebeling more than 15 years ago at an entertainment marketing conference, describes his friend as a “super hero.” Fraction has a theory of how Ebeling acquired his “super power” which he describes as problem-solving: “I kind of think it’s something he got from surfing. Who are you, in the face of a wave, before the whole of the ocean.”

Ebeling’s wife, Caskey, attributes her husband’s inner strength and confidence to a lesson in adversity at the Air Force Academy that “made him feel like he could handle life’s pressures.”

“I learned structure at the Airforce Academy but I learned independence and self-drive at Santa Barbara,” Ebeling says. “It’s also the ability to interact with different people from different places—that is definitely a skill set I’ve taken.”

Ebeling recalls a class about French Existentialism taught by the late Ernest Sturm, Professor of French and Italian, that changed his worldview.

“I think in my attic some place I still have my class notes and the books,” he recalls. “It was on Camus and Jean-Paul Sartre and it was the most influential class I’ve ever taken. I talk to my kids today about The Stranger and Camus and what that means.”

You see signs of this impact everywhere, from the quote by Camus on the Not Impossible website (“The absurd is borne out of confrontation between human need and the unreasonable silence of the world”) to the Power Point by Horace Mann in his presentation (“Refuse to die until you have won some victory for humanity.”) In his book, he quotes the designer/futurist Buckminster Fuller (“You never change things by fighting the existing reality. To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete.”) Even in casual conversation, Ebeling is wont to reference St. Francis of Assisi (“Preach always. Use words as little as possible”). Ebeling’s philosophy binge began when he was building his production company. “At that point in my life, I was reading a lot of self-help books,” he wrote. “I was a sponge for anything that helped you have a positive attitude.”

The Power Point aphorisms in Ebeling’s presentations and literary references in his conversations could suggest a philosopher. Then again, they are also the tools of a motivational speaker. Onstage, he radiates the confidence and charisma of Oprah celebrity protégés from Doctors Phil to Oz, but one-to-one, he’s really no different. This is, after all, a man who spends eight and a half of the 245 pages in his book thanking every important individual in his life, from his wife, mother and sons to a cavalcade of bit players who figure into his life story. Some are probably a little too personal to share with the world, like a text to a spouse or a note you’d slip into your child’s lunch bag, which may be precisely the point. They seem to be written less for readers plural than for one in particular.

"There's no other company in the world that's doing what we do," he says, "I wish there was."

Ebeling doesn’t just wear his heart on his sleeve; he extends it almost reflexively. One of his many mantras, “Leap and the net will appear,” is a reflection of Ebeling’s big-hearted intentions but is it sustainable as a business model? Is there a point where even the most positive man in the world must just say no?

THE NEXT CHAPTER

Mick Ebeling would be only too happy for you to rip him off. “There’s no other company in the world that’s doing what we do,” he says. “I wish there was.”

Yet as much as he would like Not Impossible to become a model for ventures with a similar social mission, there is one practical pitfall: Ebeling’s inability to replicate himself. Ebeling remains the face of his organization, its most compelling storyteller and its driving force. Like the most effective leaders, he also knows his limitations. Perhaps this explains why, nearly a year ago, Ebeling hired Adam Dole as Managing Director of Not Impossible Labs. Dole had the lofty, hope-filled cred from his experience as a Presidential Innovation Fellow in the Obama White House as well as the practical strategic experience from working with organizations like the Mayo Clinic and NASA.

“I have never worked with anyone who exudes the sense of urgency that Mick does for solving humanitarian absurdities,” Dole says. There is, for example, a medical device the company designed that “has the potential to impact millions of patients.” Clinical trials are just beginning but FDA approval would “open up the possibility for new revenue streams and distribution channels that will enable us to impact many more patients in the future.”

Dole says “We have set our sights on massive growth in the coming years,” but he acknowledges that “There is no shortage of absurdities out there in the world and we have to be disciplined and diligent about which ones we decide to invest in.”

Dole plays the pragmatic, bottom-line businessman to Not Impossible’s visionary founder. Together, they represent “the yin and the yang,” to use another preferred Ebelism. In that balance, perhaps Ebeling has found a way to focus his time on doing what he is most passionate about, making the impossible possible.

“I feel so lucky that I discovered this because there’s nothing [else] I ever want to do ever again,” Ebeling says. “You are going to have to screw the coffin shut to get me to stop doing this.”